Fish compatibility is the most difficult subject in the industry, and the greatest topic of controversy among professional aquarists. Those of us at the Aquarium Professionals Group with many years of experience are still learning about the subject. The problem is that there are no definite right or wrong answers when it comes to deciding which fish we can keep together in an aquarium. Some cases are obvious . . . or are they? No professional aquarist in their right mind would recommend keeping huge freshwater Oscars with tiny Neon Tetras. Yet the fact remains that our most experienced aquarists have seen the most improbable combinations of fish kept together without any compatibility problems. So as we began drawing up the first draft of our articles for this up-date, the question was raised: Why bother discussing an aquarium issue that is so conceptual that there are no definite facts that can be related to the reader?

The answer to that question is simple, although the execution is not so easy. There are far too many unknowledgeable and/or unscrupulous pet and aquarium stores out there that don't know or may not care when they sell you incompatible fish. They want your money, and most do not offer adequate guarantees that cover for example, one fish eating another. We therefore felt we should at least provide some basic guidelines and tips to help ensure compatibility. These generalities should be used as a tentative guide, keeping in mind that when it comes to fish compatibility, nothing is written in stone!

(joke),When shopping for a fish that you're unfamiliar with, ask a lot of questions. Take the time to look the fish up in an aquarium reference book.

If you're shopping in a new store, make friends with the staff and owners. They may develop a case of "conscience" before selling you a fish that's incompatible with your aquarium or another specimen you want to buy.

Check the livestock guarantees of the store you're shopping in. If they only have a 24 hour guarantee, or no guarantee (common these days with saltwater fish), they may have no incentive to guide you carefully when it comes to compatibility. If the fish you buy causes trouble but doesn't die, they may not take it back for credit.

As a general rule for all saltwater aquariums, and most freshwater tanks, new fish should always be added in groups of two or more. This helps to spread out the aggression in the tank. An aggressive fish that's already in the tank cannot chase two or more newcomers at once. This gives the new fish an occasional break in the action and allows them some recovery time.

It is important not to confuse aggression with hunger or feeding habits. Just because a fish has a large mouth or eats whole fish in the wild, does not necessarily make it aggressive. Piranha are actually quite peaceful. So are most Moray Eels. African Cichlids are primarily herbivores (vegetarian), but are extremely aggressive. Even us so-called "experts" have a tendency to get a little anthropomorphic about our fish, by attributing human characteristics to our finned little buddies (see . . . there I go!). Fish behave almost entirely through instinct. An instinct to strike out at a tank mate that's invading a territory is not "acting mean". It’s simply an instinctual response to an external stimulus. That isn't to say that fish can't "learn". Anyone who's ever seen their fish splash water in the tank in order to get fed would disagree. In most cases though, what we perceive as mean or cowardly behavior, is simply instinctual behavior that is genetically programmed. The fish was literally born to follow these behavior patterns. Unlike dogs and cats, there is no proven way to modify instinctual behavior in fish.

Nearly all saltwater fish, with few exceptions (such as seahorses), are aggressive to some degree. They come from a hostile environment, and behave accordingly.

All aquariums have a pecking order among their inhabitants. There will always be an "Alpha" specimen at the top of the order, and a series of less aggressive "Beta" specimens all the way down to the bottom of the pecking order. If you remove the most aggressive fish from an aquarium, another will take its place at the top of the pecking order. Generally, as long as no actual bodily damage is occurring, it's best to leave well enough alone. Even an occasional nipped fin is no real cause for alarm (Missing fins are another story).

Nearly 99.99 % of all saltwater aquarium invertebrates do not belong in a marine fish-only aquarium. Invertebrates are the natural foods of the fish. The one good exception are hermit crabs, which are somewhat protected by the seashells they carry. You can experiment with anemones, and maybe a lobster or shrimp, as long as you understand that it's an experiment, with a possible disastrous (and expensive) outcome.

As a general rule for both freshwater and marine fish, if you want to combine several specimens together that you're unsure of in terms of compatibility, use the following plan of action:

1. Determine the relative aggressiveness of each specimen you want to put together on a scale of one to ten by reading up on each and asking questions.

2. Buy the two most peaceful fish FIRST, and get the largest specimens you can find.

3. Each set of fish that follows should be a little more aggressive than the first, and smaller than the last set you added.

4. The last fish that you add should be the most aggressive, but also the smallest of the desired group.

5. Synopsis: Add the least aggressive fish first and make sure it will be the biggest fish in the tank. Add fish in order of increased aggressive behavior with each fish being smaller than the last. The most aggressive fish is added last, and should be the smallest specimen in the tank. Using this method allows the more peaceful fish to set up their territories first. By making the more peaceful fish larger, you give them a fighting advantage over the more aggressive species.

When considering the purchase of larger, more aggressive, or very active fish, beware of any definite statements made by salespeople that the specimen will be compatible. Statements like "Oh that will definitely work.", as opposed to "It should work." deserve a second opinion. If you're in doubt, they should be too.

Unfortunately, it is all too common to see incompatibility in action in the tanks at a pet or aquarium retail store. We've seen plenty of cases where every fish in a pet store tank is hiding except one, who's calmly cruising the tank looking for trouble. This can be of educational benefit though, in that one can learn first-hand about certain species that don’t get along with one another.

As a very loose general rule, with many exceptions, fish that are extremely hyper-active may stress fish that are extremely peaceful and slow-moving. Use caution, and watch how the other fish in the tank react to the fast-moving specimen.

If a fish is alone in an aquarium, find out why it's by itself before you buy it, even if it looks like a great specimen. It very well might be in "jail" for a serious felony or two.

Seahorses are rarely compatible with other saltwater fish. Freshwater Bettas (Siamese Fighting Fish) are never compatible with each other, and are rarely compatible with other long-finned fish or very fast-moving fish. Discus (freshwater) are extremely difficult to keep, and will rarely work in a community tank. Killifish (freshwater) should be kept by themselves in a small tank, and are not usually compatible in a community tank.

Fish with large mouths relative to the rest of their body usually EAT OTHER FISH! A Frogfish, Angler, Toadfish, or Stonefish may be cute in a homely sort of way, but they can swallow another fish nearly two and a half times their size! If you have small fish, some other fish to look out for in saltwater are: Groupers, Lionfish, Snappers, Jacks, large Triggers, Trumpetfish, and large Wrasses. Some of the fish to be cautious of, if you have a peaceful freshwater community tank, are: Scats, Pacus, all large Cichlids, Gars, Arowanas, Tinfoil Barbs, Bala Sharks, African Cichlids, and even Silver Dollars. Remember that even if the fish is a small baby specimen, it’s going to grow up!

If all the fish are crowded together on one side of the tank, and one fish is at the other end of the tank, that lone fish is probably aggressive!

Another sign that there’s an aggressive fish in a tank is if one or more fish are lying on their sides or nose-up at the surface of the water. This is a submissive posture. Watch the tank for a while and eventually, you’ll see the "culprit" go up and nip at the fish that are submitting. PLEASE NOTE: The reverse could also be true in this case. The store may have put one or two specimens in the tank that are too peaceful to fit into that particular community.

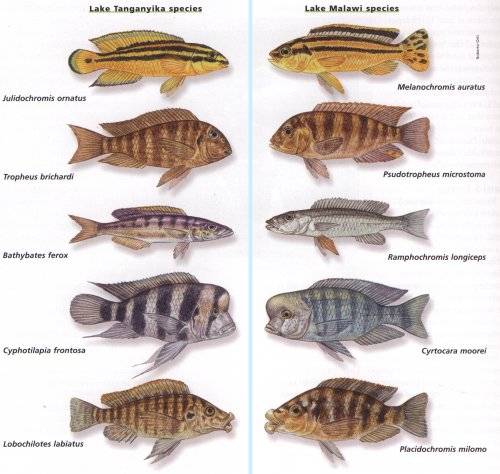

(We hesitated to include this) Taxonomy is the classification of organisms in an ordered system that indicates natural relationships. Fish (as well as all other living things) are classified by comparing their anatomical, physiological and behavioral differences. The more similarities there are between two species, the more closely-related they are considered to be to one another. Animals are classified in the following order: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus and Species. For example: Humans are classified as follows: Kingdom-Animalia (Metazoans), Phylum-Chordata, Class-Mammalia, Order-Primates, Family-Hominidae, Genus-Homo, Species-sapiens. Our "specific name" is Homo sapiens. Our common name is "Human". Taxonomy can apply to fish compatibility when you are considering purchasing two different fish that are closely-related (in the same Family or Genus). They might not get along if they are very similar in shape, color, feeding habits or behavioral patterns. This is truer in saltwater, where fish that belong to the same Genus will often not get along. In freshwater, larger, more aggressive fish that are also closely related may not be compatible with one another. We are in no way stating that any two closely-related fish are incompatible. In freshwater aquaria for example, most of the smaller, peaceful-community fish should be kept in groups or pairs. We are only saying that if you have a marine tank, or a freshwater tank with larger fish, caution should be exercised when considering a purchase of fish that belong to the same Family or Genus as a fish you already own, or another you’ve considered buying. If in doubt, give us a call.

Other factors to consider when buying two fish of the same Family or Genus, are:

The size of your tank (The bigger the tank, the more space there is for territories) The amount of decorations you have in your tank (Are there enough caves and hiding places? Sometimes buying more decorations with a new fish helps to establish new territories.) Do the fish come from the same geographical location? (If the answer is yes, they are less likely to get along.) Do the fish have very similar body shapes, coloration, or markings? (Even fish that are not closely-related may not be compatible if they look similar to one another.).

In most cases except one definite exception, two saltwater fish of the same species may not be kept together. Exceptions to this are some smaller, relatively peaceful marine fish such as Percula Clowns, Skunk Clowns (but not most other Clownfish), most Gobies, Blennies, some Damsels, and a few others. In some cases, marine fish of the same species may be kept in groups of three or more, but never in pairs. Exception: Two marine fish of the same species that were captured together in the ocean, and are being sold as a "pair" are always compatible if they’re in the same tank together at the store.

In freshwater, be careful buying mated pairs of Cichlids, Angelfish, large Gouramis, or any other fish if you have a peaceful community tank. Depending on the species, breeding pairs of fish, even smaller specimens, can get aggressive when it’s time to breed. By the way, occasionally there are "mated pairs" of saltwater fish offered for sale. If you love the fish and they’re healthy, by all means, buy them. Just don’t expect them to breed in captivity. The odds against them actually producing are greater than your odds of winning the lottery.

If you’re replacing a fish that died with another of the same species, always remember that two fish of the same species may not exhibit the same behavior. If you had a peaceful Humu Trigger, the next one may turn out to be "mean". If the last Blue Tang you had was aggressive, the next one you buy may be a "wimp". Just when a supposed "expert" claims that a certain fish is peaceful, someone comes along with a story about the same fish that became a holy terror in their tank!

If you have live plants in a freshwater tank, always ask if the fish you want eats plants.

If you have a freshwater tank, beware of buying brackish water fish for your aquarium. Brackish water fish are species that inhabit delta, marsh, coastal estuary and saltwater wetland ecosystems, where rivers feed into the ocean. These fish live in water that is slightly salty. Although they can survive for a while in 100% freshwater or saltwater, they will eventually die or do poorly if they do not get a fair amount (but not too much) salt in their water. This level of salt is too high for most freshwater fish, and too low for saltwater. Almost all aquarium and pet stores keep a wide variety of brackish specimens in their freshwater aquariums. Unfortunately, many of these stores will rarely inform you of the special requirements of these fish. They are: Archerfish, Scats, Monos, Anableps, all Gobies, Mudskippers, Walking Catfish, most Puffers (with only two true freshwater exceptions), most Mollies, Silver Sharks (a catfish species), Half beaks, Psychedelic Eels, Reed Eels, Bamboo Eels, and nearly all Pipefish (There is a true FW Pipefish, but it’s extremely rare).